S2 Episode 14 Rebel Botanists bonus

I met Elizabeth Richmond of the Rebel Botanists in London, she had come here for the Restore Nature March. (You can see some photographs from the rally below) We found a quiet spot, well quiet apart from the bells, to talk about the work of chalking the names of wild flowers onto pavements.

As you will hear she has become fascinated by the Latin names, which can sometimes seem quite alien but not in the hands of the Rebel Botanists, they love to unlock what they mean, showing how they can tell us about the plant and its uses and give us connections between plants. As you will hear in the interview Liz takes her chalks everywhere so though based in Plymouth, she has chalked all over the country. You can also hear how it all started in a time when she was able to stop and just observe nature.

As a teacher you can hear how Liz is well aware that we all learn in different ways and this is just one way to awaken people’s curiosity which is often the best way to start. She is a great supporter of the idea to have a GCSE course in Natural History, saying when she chalks people of all ages stop to ask her about the words and the plants.

This is a bonus episode that has literally grown out of Janet’s plant story and an offshoot about the GCSE course. And if you hear an episode and think there is something else connected that I could follow up, do get in touch: sally@ourplantstories.com

Liz mentioned that when she began she was carrying books around with her to identify the plants, and when I met her she had this Collins Gem Guide to Wild Flowers in her bag! However there are also apps you can download and she mentions SEEK by iNaturalist and another called: PlantNet.

Transcript of the episode

I called this podcast, Our Plant Stories, for a reason. My hope is it'll grow and develop as listeners share ideas. And that's how this bonus episode came about. We've been talking about our knowledge of plants. Can we name the ones we walk past every day? And if we could, would that increase our respect and understanding of nature? Mary Daly messaged me saying, There's a group locally to me that write in chalk the names of the plants growing in the nooks and crannies around the town. I was intrigued and after a bit of research by both of us, I was in contact with the rebel botanists. I think sometimes the Latin names of plants can seem a little intimidating, alienating, but not in the hands of the rebel botanists.

Latin names are really interesting. So, for example, I mean, the first... It's become more of our symbol, the daisy, become our symbol really. But the first Latin name we all learned was Bellis perennis, which is the Latin for the daisy, which actually means forever beautiful. So the perennis bit comes from perennial, it comes back all the time. And bellis is beautiful. So, you know, you can start to translate the Latin quite easily and get more of an understanding of that plant.

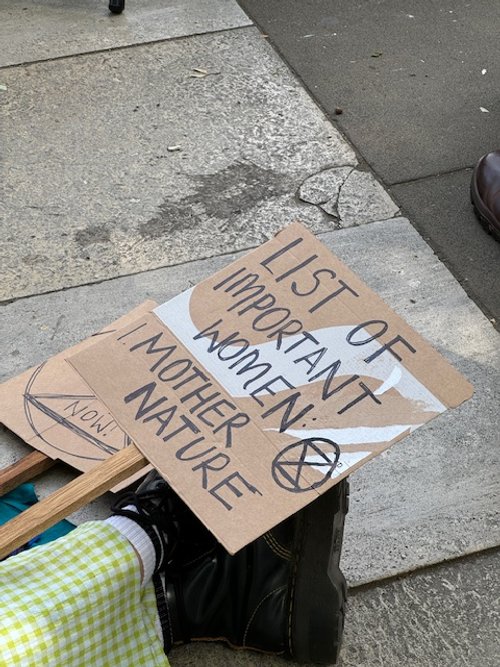

Meet Elizabeth Richmond, who likes to be described as a rebel botanist. I met her recently in central London. She'd come here for the Restore Nature Now march. 100,000 people, 350 environmental groups coming together, including charities like the National Trust and the RSPB, alongside direct action groups like Extinction Rebellion. Their message to politicians to act more decisively and robustly against the biodiversity crisis. Liz and I found each other amidst the crowds by the statue of Gandhi in Parliament Square and we headed to a quiet spot so she could tell me about the work and when it all started.

We formed at the very beginning of May 2020, it was during Covid and I had just stopped working, obviously because everyone sort of stopped working and some people felt... that was a bad thing but for me luckily it was a great thing because I just went walking and it was the first time because I'm a teacher and I'm really busy I've got lots of commitments but it was the first time I could just stop and not have to think about looking at my watch so I used to just go walking in the park where I live and just walk I think I'll go for walk for an hour but I end up getting back home at four or five hours later and I just felt it was the most relaxed I've ever felt it was amazing and During that time actually, Chris Packham and Megan had started doing this isolating bird club, which was this thing on their internet, which they did with their phones from his back garden. So I woke up in the morning, listened to this thing at nine o'clock over a cup of tea, and I was listening to what he was talking about in his garden with all the birds in his garden. And I thought, that's amazing. And then I took that information out when I went walking, listening to the birds in the park. But then I soon started to connect the birds with the habitats. So for example, I remember seeing a group of like gold finches having a dust bath, you know? And I thought, oh, that's amazing. And then I was looking at blackbirds and then I started veering off the path in the park. And then I would, like a 10 year old or something, I would go off the path and then I'd be walking amongst the trees and whatever. and then sitting on a log and then wait. And then the birds started to come back and not take any notice of me anymore because I was just really still. And then I was just watching the birds and then as I say, then I was looking at what, which trees the birds tended to be in and their habitat. And then I started connecting things. And then, I mean, I've always liked nature, but I've never, it's that stopping and really looking at things. So then I started looking at the trees and then I started looking at the plants along the way and then thinking about, well, actually, what is that called? lots of little yellow flowers and you think oh buttercup and they're not all buttercups there's hundreds and hundreds of yellow flower species so I just started to get interested into it and then I'd get home and then what I'd learned some of it like you do you forget nothing I'm like what was that again you know so I thought how can I try to remember this and then it was It wasn't very long afterwards, I was on the internet, and I saw this Frenchman in Toulouse who was a natural history teacher, I think, and he went out writing the names of a plant on the streets. And I thought, what a brilliant idea. So I got a piece of chalk and I went out and I thought, if I do that... that will help me remember the name of the plants. So I went out and I started looking them up and then I thought, oh, what's the Latin name for this? This is really interesting. And that's how it started. And then when you use the Latin, you start to link the different flowers. You start to see the connections. So yeah, that's really how it all started.

You said you were a teacher, what do you teach?

I teach, I'm an English teacher and an art teacher. Currently I'm teaching art.

Interesting. So language is important to you? Words are important to you?

Yeah, absolutely.

And did you know a lot of these plants or did you literally have to go yourself and look them up and learn the names then? They weren't some of them you knew or?

Um, well, we all know a daisy, we all know a dandelion, don't we? But I didn't know the Latin names. And you know, you can, I mean... You think you know more than you do, but you don't really. I mean, I went out and asked somebody, I think, oh God, what kind of tree is that? Is that an elder? Is that, no, actually I don't really know. It's surprising that you, what you don't know. So, I mean, I've always been into nature, but again, stopping and recognizing what the individual species are. And I just thought, actually I don't really know half of these things. So, I pulled out wildflower books and tree books and I started walking in the park with the books in my bag. quite heavy when you're carrying a load of books around. But then as we were allowed to have an extra person walk with you or whatever, my friend Gay started to join me. She thought, well that sounds really good Liz, I'll come down and join you. I said fine. And then it gradually built up and then another friend joined and another friend joined. So there was about five or six of us going out, you know, doing this, walking around. But I remember when we first started going out, it was just myself and Gay. And we walked through the park and I named a yew tree. and we were walking along doing some chalking, this guy shouted to us and I thought, oh no, I'm in trouble now, you know, and he said, oh, did you just chalk that tree? And I said, yeah, and he said, amazing. He said, what a brilliant idea. He said, I run through this park every day. He said, I never knew that was a yew tree. And I thought, really? You didn't know it was a yew tree? So, and then I thought, actually, there's something in this. So then I really, really went for it then. I thought, right, then I started naming that in name and it just built up and then started making connections, you know, saying like oak trees, you know, how many species that they can sustain and things like this. So yeah, and it just got really, really popular and a lot of things, you know, we're all trying to support the planet, aren't we? We're all trying to save this wonderful planet and help nature. But some things do sometimes, I don't know, bring forth anger. Unfortunately people moan when they, whatever. But actually we never had anybody moan at us, so we never went up to anybody, we just did all our talking. And then people just came up to us and they would ask us about the Latin, and then they'd ask us about the Latin names and oh why are you doing this? And you know then we'd tell them because we're actually showing what the names are and how we walk past these little plants every day and we don't know what they are. We don't offer them, we don't look at them. and people just thought it was great.

Do you often pick plants that are literally growing out of the pavement, growing in the kerbsides? Is that part of it for you?

Oh, that's absolutely, yeah. I mean, we aim to do urban talking, that's what we're all about, because that's where it happens. I mean, people that go into the country or go into the woods probably are already into nature, they're already liking nature, you know. But people who are just walking on the streets, you know, city people, they just don't see half of what's there. And that's why we felt that we needed to raise that awareness. So rather than just walking along, you know, look, look and see what's around you. So see the daisies, see the, you know, the symbolaria moralis over there hanging off the wall. That is impressive. And you know, we're under a London plane tree and the bark of a plane tree absorbs all the pollution in the city. You know, these are the benefits of trees. and this particular tree. So that's what we were trying to do. Get people to notice the plants and then when people stop and look, get people to kind of understand the importance of them. But I think just that the point is if they stop and look and they learn the name of a plant, they're making a connection. And I think once you make that connection, you start to respect that plant.

Tell me a bit more about the Latin, what you discovered when you actually gave them the Latin names.

I think just Latin names are really interesting. So for example, I mean that the first... it's become more of our symbol, the daisy, become our symbol really. But the first Latin name we all learned was bellis perennis, which is the Latin for the daisy, which actually means forever beautiful. So the perennis bit comes from perennial, it comes back all the time, and bellis is beautiful. So, you know, you can start to... translate the Latin quite easily and get more of an understanding of that plant. But also you see the connections, so things like dandelion, so Teraxacum officinal. So usually Latin names are always binomial, which means two-named. So at the end, officinal normally means that if a plant is officinal, then it's identified herbal medicines. So you know learning the Latin is really interesting, it's really important I think. People don't know Latin and they'll say well what does that mean you know you say well if you see a plateless aficionado it's connected to medicine you know we need those plants.

Will you write the common name as well?

We write the common names as well yeah absolutely because people think what is that? They won't have a clue. So yeah like the Cymbalaria Muralis over there that's Ivy-leaved Toadflax. So, and most people don't know what that is either. But it's those lovely little purple and yellow flowers that crawl up the walls, that come out of the cracks in the walls. And they're everywhere actually, but people walk by them. But like you said, I mean, a lot of the times it is the, we're not looking at the urban plants in terms of people putting plants in planters. We're not interested in that. It's about those little plants, those little wild plants that are crawling out of the cracks. It's what we love.

Tell me about some of your favourite conversations you've had with people who've stopped to talk to you while you're chalking.

Well, we've had loads actually. I mean, as I said, what's really good about this movement, which we just didn't anticipate, it's something that I started just doing it for me, and it's just kind of moved, it's just developed itself, it's amazing. But I think what's really been good for all of us that are involved with this is just that you don't get anybody moaning at you. People love it. People absolutely love what we do. All ages? All ages, absolutely. And sometimes you would think, because we chalk on the floor, you'd think that would really just appeal to the kids, but no, adults love it. And I think because we don't put anything derogatory, we don't chalk anything derogatory, it's always about education, it's always about education, so it's educating people about what the plants are, the Latin and their connection to biodiversity. I think people just become... It opens the door to curiosity, that's what I always say. And then once somebody's curious, they want to know more. Whereas if you go up to somebody and you force something on them, you know, here's a leaflet about this and whatever, they're kind of like, oh, I don't know, you know. But we never approach people, they just approach us. And often it's the Latin that pulls them in, because they want to know more about it and why we're doing it. But they know it's kind of fun. I mean, yesterday we were in Richmond. and it's, you know, I mean, this house, we would look, the houses there are like 16 million pounds, you know? So, you kind of think sometimes that people might think, oh, we don't want this riffraff on our streets, you know, but actually we had some amazing conversations and just walking around with a rubber botanist sign, people walked up, said, oh, what's this? What's going on, you know? And then in one of the entrances to an area, beautiful garden area. on the top path I put walk into nature and then three quite young people came up and she looked at me and looked at the notice and she said oh my god look at that walk into nature and then she looked at the park and said come on guys let's go down here I mean that's amazing isn't it so all sorts of things come from this and I just love it.

You do this around Plymouth, is that right? Is that where you're based?

We're based in Plymouth, yeah, but we do it all over, so even if we go on holiday, it's like, take your chalks with you. Chalks are part of our stuff we put in our bags.

You've got your bag beside you, have you got chalk in it?

Actually, no, because I've just given it to Ken to look after, it's a big box of chalks. So, oh gosh, have I got one piece of chalk actually? I might have.

Liz is just rummaging through her bag now. I'm feeling confident that she is going to suddenly produce a piece of chalk because...

I think just because I haven't... Usually I carry a bag of chalks with me in my bag, but because we've come up here and actually sadly one of our rebel botanists died in March and she was really passionate. I mean she was just so passionate about this movement, she really was. And we planned to come to London. and we planned it together, you know, and to do the Richmond Park walk. So, she had a big box of chalks, so after she passed away, I took those box of chalks and I brought them with me, but they're quite big, so I've got them in a bag and now I've given them to Ken because they're just like... So for the first time, yeah, I don't think I've got... the chalks in my bag. I'm really sorry but we can always get them. They've all got their chalks with them over there. Yeah.

Do you, have you, has anybody in any other parts of the country followed your example? Have you managed to kind of get other branches going?

Oh yeah, I mean, we get messages through, so we've got a website which is rebelbotanist.org, we've got a Facebook page and we recently went onto Instagram and people message me through Facebook and say, oh could we do what you're doing? And I'm like, yeah, go for it. So yeah, I really encourage people to do it, you know, it's great. I mean recently there was a group from Chumley who sent me a message and they said can we do this? I said yeah, go ahead and do it. Are you sure we won't get arrested? I said well, what are they going to arrest you for? Chalking Latin on the pavements? I mean, you know, it could happen I suppose but let's hope not. I've not been arrested yet. I mean I've chalked outside of Westminster, I've chalked all over the place and I've in front of policemen with their guns and they just look and smile and walk away. So far so good. But yeah, I've had several people who have followed our example. I think the one that was the furthest away was in Massachusetts in America. And I said, if you do this, they said send me some pictures, and they did. And a couple of families with their children in a shopping mall area of Massachusetts, they sent me the pictures, and I thought, oh, that's amazing.

That must feel so good to think you have actually really encouraged other people to go out and do this.

Yeah, yeah, it really is. But I think, for example, like Gay, she's always saying to me, oh, I thought that more people would go out and do this, there'd be groups in every city. But actually... I think people are not very brave. I mean, they say to me, oh, can you come up and help us do it? And I think, well, let's get a book, you know, or just get an app. It's easy. They kind of like us to go up there and start them off. But I think other things have come from it, which I'm really pleased about. So I've got so many people that have sent me messages saying that how they've changed their garden practices. So a lot of the key things I say about Rebel Botanists is we're focused on nurturing wild plants, the native wild plants, Our native wild plants have taken thousands of years to develop here and so is the biodiversity that relies on them. So those are the key species that we need to protect. And so also not using pesticides and definitely no plastic grass. I hate plastic grass. So there are certain things that I sort of talk about on the Rebel Botanists site. So lots of people have come back and said, you know, I've changed my practice of how I garden. flowers I'm putting in there and you know I'm doing it more wild and there was a lovely lady who follows us quite avidly actually and she knows like throw seeds in the hedgerows all around the area she lives in Wales. It's just fantastic so lots more comes from it just some people chalking on the streets.

Where did the name come from?

Well it was me I made that name up so when we started doing it we knew we had we had something going you know and I thought we need a So I thought well, we're doing botany and then at first I kind of was thinking it's a little bit rebellious It's a little bit kind of off the wall, isn't it? I was thinking like maybe punk rebels and I thought no because I'm a bit of a Vivian Westwood fan as well so I thought no punk doesn't work and then and then I was I Think a couple days later. I was playing a David Bowie thing and I thought rebel So that was it rebel botanists and it's yeah people love the name.

What do you feel about the idea to have a GCSE in Natural History?

Oh I love it, absolutely love it. I mean I read about it quite a few years ago now and I thought then, you know, this is lacking in our curriculum. And the government are really pushing for everything to be STEM. You know, that's fine, that's fine, but you know it's not just about that. The arts, they're cutting back on the arts. and from the arts you've got creativity. As well as having mathematicians, as well as having scientists, you need creative minds and it's wrong to be pulling back on those subjects. Natural History, I've watched David Attenborough, which is one reason why we went to Richmond yesterday. I've watched David Attenborough since I was a child. He's the longest teacher I've ever had. I have loads of DVDs at home and I think, right I must learn up on this and I pull them out. and I watch them and he's just like a really amazing facilitator. You know, he's got a great team with him as well, let's not forget that, but his facilitation of how he presents it and how he narrates it really resonates and I've worked with a lot of different students. Some are very rebellious in themselves and but I've never come across even some of the worst students I've had who don't like David Attenborough. In fact, a colleague of mine once, I remember one time she had a terrible group. I mean, they were just awful, kicking off and it was just dreadful. And she came into me and she went, Liz, have you got a David Attenborough DVD? And I said, yeah, yeah. So they all sat watching David Attenborough and they all calmed down. There you go. Ha ha ha. It's incredible, isn't it? So do we need natural history? Absolutely, absolutely. It embeds everything that it's about where we are, where we've come from and where we're going.

So we're in Dean's Yard, which is why you can hear the bell going in the background. Although it's amazingly quiet actually, isn't it? Well, it was quite quiet, and then the bell started going. But if we cross, now this is what I think of you as doing. So we're kind of, we've got some steps going up and we've got some plants that are growing in the crevices, growing up the steps. So what am I looking at, Liz?

So you're looking at, see I was right, even across the other side of the road, it's Cymbalaria Muralis. And if you look at them carefully, they kind of look like little snapdragon flowers. So they've got, wrong glasses, can't see with my sunglasses on. So they've got a central yellow section. They've got two tiny little purple petals that stick up like little rabbit's ears. And then they've got three bigger ones coming out from the bottom. They're very pretty, I mean they're tiny, they're about a quarter the size of my fingernail. They're really small. And they just, you always find them on old walls. They creep up and they self-pollinate actually. And they creep up and they embed their little roots into the cracks and crevices of the walls and hang down. And because they're on walls, that's where the muralist comes from, as in mural. And symbolaria, symbols. So people say they look kind of like symbols, but I’m not sure, its the most common one here. It's creeping all the way along these steps. Now one thing I didn't mention to you before is that you know I started going out with books but then we thought we were carrying all these books around with us so we've got some apps now that we use on the phone and that's good because it encourages younger people to get involved as well. So we use an app called Seek. So it's called Seek, as in hide and seek, and you click onto it, and you point the camera at the flower, or the plant, or the tree, and then hopefully, it should tell you what it is.

I was gonna ask, are there any books that you recommended?

Yeah, I mean, I use, there's a little wildflower book I've got in my bag, actually. I mean there are quite a few different books that you can get. But I've got this little tiny Collins gem guide and they do lots of guides on trees and whatever. This one on wildflowers is quite good actually. So it gives you what the flowers look like, the leaves. It tells you the name, gives you the Latin name, and then gives you a little bit of information about them as well. So, yeah.

You can tuck that in the pocket of any jacket, couldn't you?

It's just really small, so I carry that around with me quite a lot. I quite like a little tiny book to refer to, it's really nice. And you can use apps like we've got this one which is Seek by iNaturalist. There's also one called Plantnet which is quite good as well. And they feed into a global database so for example Seek goes into National Geographic and I think it's the University of California and then they collect all that information so if you've got the location on they'll know that you've found her. a symbol or a muralist in the middle of Dean's Yard in London. So then they collect this data, so you become a citizen scientist as well, which is great. And it records everything across the world and where it is and how many there are, etc. So it helps.

So you feel part of something much bigger when you do this?

Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, yeah. So if you use the online apps, that's what you can feed into, which is great. A lot of people like doing that. or you can just use the little books, which is nice as well. But we all learn in different ways, so. But I think, you know, for us as well, because you look at the plant and then you chalk it, I think in doing that it helps you to remember what it is. It did for me anyway. As soon as you write down the name, that helps, doesn't it?

For me as well, the way to learn is to write the name down. When I was learning, when I did my RHS Level 2 and you had to learn a certain number of Latin names of plants every single week, the writing down was really important for me.

I know, because if you just read it out of a book, it's like a death by worksheet, isn't it? That's what we say in teaching. stick does it? And I imagine if you write it big in chalk then it really helps. I know and you because you're doing it you've got that kinesthetic learning and you've also got the visual learning so you know yeah.

So if you had chalk now you would literally take this plant and you would write its name.

I would write its common name and its Latin name around it yeah I mean it's nice if you've got nice writing as well so you know we try to get nice writing.

Liz and I headed back to Parliament Square where she retrieved the box of chalks and even though there were no plants in any of the cracks or crevices, she showed me how she writes and draws on the pavement. So, head over to the website, ourplantstories.com or my Instagram account, ourplantstories.com podcast to see the photographs. I'm reminded of Mary Colwell's comment in the episode about a GCSE in natural history. She said... You're not asked. I'm not asked. David Attenborough isn't asked. Anybody isn't asked to save the world. We're only asked to do what we can do. Thanks to Mary Daly for the tip-off about the rebel botanists and Liz Richmond for taking the time to talk to me.

Our Plant Stories is an independent production presented and produced by me, Sally Flattman.